Einstein's Theory of General Relativity

In 1905, Albert Einstein determined that the laws of physics are the same for all non-accelerating observers, and that the speed of light in a vacuum was independent of the motion of all observers. This was the theory of special relativity. It introduced a new framework for all of physics and proposed new concepts of space and time.

Einstein then spent 10 years trying to include acceleration in the theory and published his theory of general relativity in 1915. In it, he determined that massive objects cause a distortion in space-time, which is felt as gravity.

The tug of gravity

Two objects exert a force of attraction on one another known as "gravity." Sir Isaac Newton quantified the gravity between two objects when he formulated his three laws of motion. The force tugging between two bodies depends on how massive each one is and how far apart the two lie. Even as the center of the Earth is pulling you toward it (keeping you firmly lodged on the ground), your center of mass is pulling back at the Earth. But the more massive body barely feels the tug from you, while with your much smaller mass you find yourself firmly rooted thanks to that same force. Yet Newton's laws assume that gravity is an innate force of an object that can act over a distance.

Albert Einstein, in his theory of special relativity, determined that the laws of physics are the same for all non-accelerating observers, and he showed that the speed of light within a vacuum is the same no matter the speed at which an observer travels. As a result, he found that space and time were interwoven into a single continuum known as space-time. Events that occur at the same time for one observer could occur at different times for another.

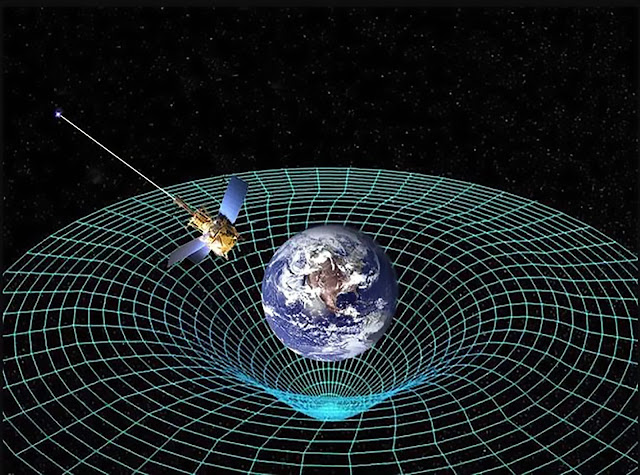

As he worked out the equations for his general theory of relativity, Einstein realized that massive objects caused a distortion in space-time. Imagine setting a large body in the center of a trampoline. The body would press down into the fabric, causing it to dimple. A marble rolled around the edge would spiral inward toward the body, pulled in much the same way that the gravity of a planet pulls at rocks in space.

Experimental evidence

Although instruments can neither see nor measure space-time, several of the phenomena predicted by its warping have been confirmed.

Gravitational lensing: Light around a massive object, such as a black hole, is bent, causing it to act as a lens for the things that lie behind it. Astronomers routinely use this method to study stars and galaxies behind massive objects.

Einstein's Cross, a quasar in the Pegasus constellation, is an excellent example of gravitational lensing. The quasar is about 8 billion light-years from Earth, and sits behind a galaxy that is 400 million light-years away. Four images of the quasar appear around the galaxy because the intense gravity of the galaxy bends the light coming from the quasar.

Gravitational lensing can allow scientists to see some pretty cool things, but until recently, what they spotted around the lens has remained fairly static. However, since the light traveling around the lens takes a different path, each traveling over a different amount of time, scientists were able to observe a supernova occur four different times as it was magnified by a massive galaxy.

In another interesting observation, NASA's Kepler telescope spotted a dead star, known as a white dwarf, orbiting a red dwarf in a binary system. Although the white dwarf is more massive, it has a far smaller radius than its companion.

"The technique is equivalent to spotting a flea on a light bulb 3,000 miles away, roughly the distance from Los Angeles to New York City," Avi Shporer of the California Institute of Technology said in a statement.

Changes in the orbit of Mercury: The orbit of Mercury is shifting very gradually over time, due to the curvature of space-time around the massive sun. In a few billion years, it could even collide with Earth.

Frame-dragging of space-time around rotating bodies: The spin of a heavy object, such as Earth, should twist and distort the space-time around it. In 2004, NASA launched the Gravity Probe B GP-B). The precisely calibrated satellite caused the axes of gyroscopes inside to drift very slightly over time, a result that coincided with Einstein's theory.

"Imagine the Earth as if it were immersed in honey," Gravity Probe-B principal investigator Francis Everitt, of Stanford University, said in a statement.

"As the planet rotates, the honey around it would swirl, and it's the same with space and time. GP-B confirmed two of the most profound predictions of Einstein's universe, having far-reaching implications across astrophysics research."

Gravitational redshift: The electromagnetic radiation of an object is stretched out slightly inside a gravitational field. Think of the sound waves that emanate from a siren on an emergency vehicle; as the vehicle moves toward an observer, sound waves are compressed, but as it moves away, they are stretched out, or redshifted. Known as the Doppler Effect, the same phenomena occurs with waves of light at all frequencies. In 1959, two physicists, Robert Pound and Glen Rebka, shot gamma-rays of radioactive iron up the side of a tower at Harvard University and found them to be minutely less than their natural frequency due to distortions caused by gravity.

Gravitational waves: Violent events, such as the collision of two black holes, are thought to be able to create ripples in space-time known as gravitational waves. In 2016, the Laser Interferometer Gravitational Wave Observatory (LIGO) announced that it found evidence of these tell-tale indicators.

In 2014, scientists announced that they had detected gravitational waves left over from the Big Bang using the Background Imaging of Cosmic Extragalactic Polarization (BICEP2) telescope in Antarctica. It is thought that such waves are embedded in the cosmic microwave background. However, further research revealed that their data was contaminated by dust in the line of sight.

"Searching for this unique record of the very early universe is as difficult as it is exciting," Jan Tauber, the European Space Agency's project scientist for the Planck space mission to search for cosmic waves, said in a statement.

LIGO spotted the first confirmed gravitational wave on September 14, 2015. The pair of instruments, based out of Louisiana and Washington, had recently been upgraded, and were in the process of being calibrated before they went online. The first detection was so large that, according to LIGO spokesperson Gabriela Gonzalez, it took the team several months of analyzation to convince themselves that it was a real signal and not a glitch.

"We were very lucky on the first detection that it was so obvious," she said during at the 228 American Astronomical Society meeting in June 2016.

A second signal was spotted on December 26 of the same year, and a third candidate was mentioned along with it. While the first two signals are almost definitively astrophysical—Gonzalez said there was less than one part in a million of them being something else—the third candidate has only an 85 percent probability of being a gravitational wave.

Together, the two firm detections provide evidence for pairs of black holes spiraling inward and colliding. As time passes, Gonzalez anticipates that more gravitational waves will be detected by LIGO and other upcoming instruments, such as the one planned by India.

"We can test general relativity, and general relativity has passed the test," Gonzalez said.

Comments

Post a Comment